The Problem(s) with living up to Expectations

- maxbentinck

- Apr 20, 2021

- 7 min read

Updated: Apr 21, 2021

The feeling of having to live up to other people's expectations is something that we have all experienced in some shape or form at one point in our life.

Sometimes this can encourage us to reach great heights and test the limits of the possible. However, these expectations, be they real or even imagined, can have have a paralyzing effect if they are not in line with our true self.

In this article, I draw from my own as well as from other experiences to explore how to come to come to terms with the inevitable pressures and expectations from the outside world and stay true to who we really are or want to be.

Something stirred in me while reading Ibram’s X Kendi’s article on the Black Renaissance in Time Magazine. It described how African-Americans are freeing themselves more and more from what the celebrated poet Tony Morrison called the “white gaze,” the process through which African Americans, by living in a society where everything gets perceived and judged from the dominant white perspective, end up also viewing themselves through that lens, and in their desire to fit in, lose sight of their own aspirations and even more importantly, who they really are.

Now you might ask, what in the world does this have to do with me, a white Caucasian man living Europe? How could I possibly understand the first thing of what it must be like to be a Black man or woman in America today? And you’re right, I don’t, nor will I ever. But what I do know a thing or two about, is what it feels like to live under a gaze, which as a disabled person, for me meant living under a “gaze of normality.”

President Obama awarding Tony Morrison the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award in the United States.

Going through “mainstream education” meant that while growing up, I was nearly always the only person who looked noticeably different whenever I came into contact with others.

Although this never prevented me from making friends and feeling socially integrated and accepted, I always felt, especially at a young age, a significant amount of pressure amid all these kids with seemingly little to no challenges in comparison, to fit in and do everything in my power so that they would ‘forget the wheelchair.”

I tried to accomplish this by constantly trying to project strength and control when with others, putting on a sunny face in all circumstances, even when I actually felt overwhelmed with anxiety and wanted to crawl under a rock. I did this, because in my book, for the outside world to consider me as ‘normal’, meant I had to perform even better than my peers, in short turn into some kind of Superman.

As you can imagine, all that took a heavy toll on me, and I regularly got sick to my stomach and threw up in class throughout the first few grades of primary school, whenever an overwhelming feeling of stress came over me upon needing a little more time than the others to master a new concept. I was born with cerebral palsy which, among other things prevented me initially from properly assessing spaces and distances. For instance, when learning how to write, as I was unable to properly see the lines on the paper, I would write each letter of my name on different parts of the page.

This happened to me on more than one occasion, especially during math class… And when it did, there was always that little voice in my head saying “you see, there’s the proof that you don’t belong after all” or questions like am I good enough? Am I normal enough?

My fear of not being considered normal, also made me reject my belonging to the disabled community. As a result, I never sought out contact with others in a similar situation; I was normal after all, so why would I possibly want anything to do with that world?

It has taken me years of soul-searching and therapy to be able to express this, let alone come to terms with my identity, which I have to admit, is still very much a work in progress.

Thinking about it a little bit more now years later, I’m beginning to realize that dealing with “a gaze”, which is obviously defined differently for each of us, is something that far exceeds the experiences of racial and other minorities like my own. It is something almost universal that everyone, to some extent, can relate to. Who after all, whether it’s in their own life or someone else’s, doesn’t have an example where some external force is pressuring you or others to act and behave in a certain way or risk not being accepted or successful?

For example, there have been many cases since the beginning of time, of sons and daughters having to forgo their dreams in the face of parental or societal pressure. I bet the first women to attend university not even that long ago, felt the full brunt of the male gaze, often causing them to feel guilty for pursuing an education and wanting more out of life than what society expected of them at the time.

While it’s true we’ve made a lot of progress since then, if you look carefully enough, it won’t be long before you’ll find another version of the gaze, passing judgment on our actions, and if were not careful, end up changing the way we look at ourselves as well..

An illustration of this was brought to my attention recently when a friend told me about how so many young mothers are being shamed, even by hospital staff, for choosing not to breast-feed their child, making them feel as though they’re bad, irresponsible mothers who are consciously impacting the health of their newborn, neglecting the fact that it’s a personal issue and that there might be very good reasons for them not to do so. If unaddressed, this judgmental gaze is often internalized, causing moms to second-guess their own choices, to the point of questioning their very fitness as a mother.

What if I told you that living under a “gaze “that can be defined as conforming one’s actions to the supposed expectations of external forces, not only can affect people in their personal lives, but the performance of companies as well.

Consider the case of the Walt Disney Company, that for almost two decades following the death of the visionary founder bearing its name, suffered from a real glut in innovation. The reason? Well, it turns out that executives at the company were fearful, even paralyzed to make decisions in Walt’s absence, and constantly asking themselves “what would Walt do”? It was as if the gaze of the great man was hovering over everyone in the organization, causing them to stay mired in the past and preventing them from making the tough calls that would ensure the company’s long-term success.

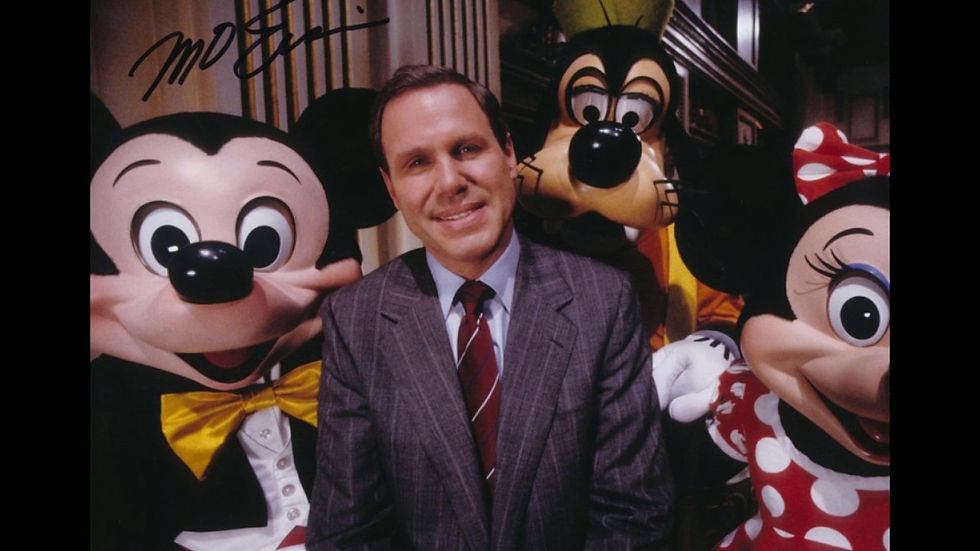

At one point, the situation was so dire, that to fend off a hostile takeover from outside investors and save the company, Roy Disney, Walt’s nephew, convinced the board to remove Disney president Ron Miller from his position and install a new leadership team, with Michael Eisner as CEO.

Under Eisner’s leadership, Disney was finally able, after 18 years, to turn the corner and liberate itself from years of paralysis that resulted from trying to live up to the imagined expectations of its deceased founder. This change in mindset, set the company on a long-term path to success, allowing them to chart a new course all the while remaining faithful to Walt’s belief in creativity and relentless innovation.

Michael Eisner is widely considered as the driving force behind Disney's turnaround, putting an end to a decline that lasted for about two decades.

Comments